The Sinking City

One of the better Lovecraft games currently available is deeply flawed. If you can look past these issues, you’re in for a fun gaming experience.

Introduction: Vote for Cthulhu

Fall weather here is bizarre as we just had our first snowfall. While the leaves are changing and I now have to deal with 30-degree temps, let’s review a game! Like many people, I play spooky games during the Halloween season. It’s been a hot minute since I’ve reviewed one, so feel free to check out Silent Hill: Homecoming, Resident Evil 2, and Resident Evil 3. This current review is on Frogwares’ The Sinking City, a game that apparently involved a messy divorce with Nacon, Frogwares’ distributor at the time. As for the game itself, The Sinking City is an open-world, action-adventure, survival horror game heavily inspired by the works of H.P. Lovecraft (that’s a lot of game genres). Fans will see influences from works like The Shadow over Innsmouth, “The Call of Cthulhu,” and Robert W. Chambers’ The King in Yellow. While many of Lovecraft’s stories have been rightly criticized for their racist and xenophobic undertones, his spin on cosmic horror is omnipresent. Interestingly, I was first introduced to Lovecraftian themes while playing Atlus’ Persona 2 back in high school. During the two-game sequel, the two parties composed of different characters learn that the world is in disarray precisely because Nyarlathotep (AKA the Crawling Chaos) desires to eradicate mankind. Since then, I’ve dabbled in the Mythos and have my favorite stories. While I played Cyanide’s Call of Cthulhu a few months ago, I was disappointed by its glitchy mechanics, even though the story had several intriguing moments. As I started The Sinking City, I was scared that I would encounter similar glitches because I accidentally fell into the ocean with no way of reaching dry land (just stay out of the water). On another occasion, I laughed when a monster followed me into a dialogue cutscene, and it stayed in the frame while my character began to float in the air. Despite these hiccups, I stuck with the game and ultimately had a great time. However, while The Sinking City is better than Call of Cthulhu, it isn’t without its own problems.

Story and Characters: Something “Fishy” Is Going On! Get It?!

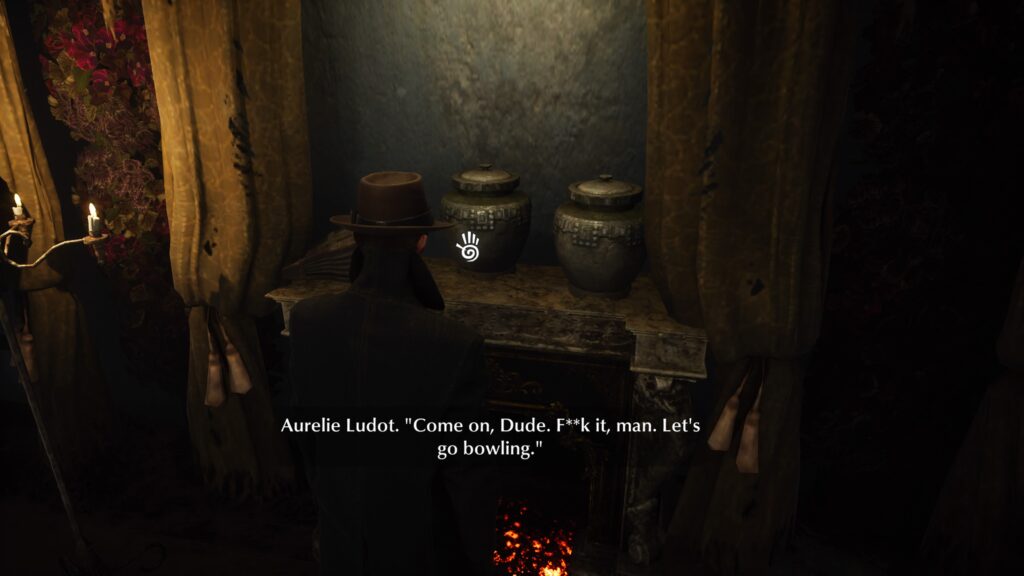

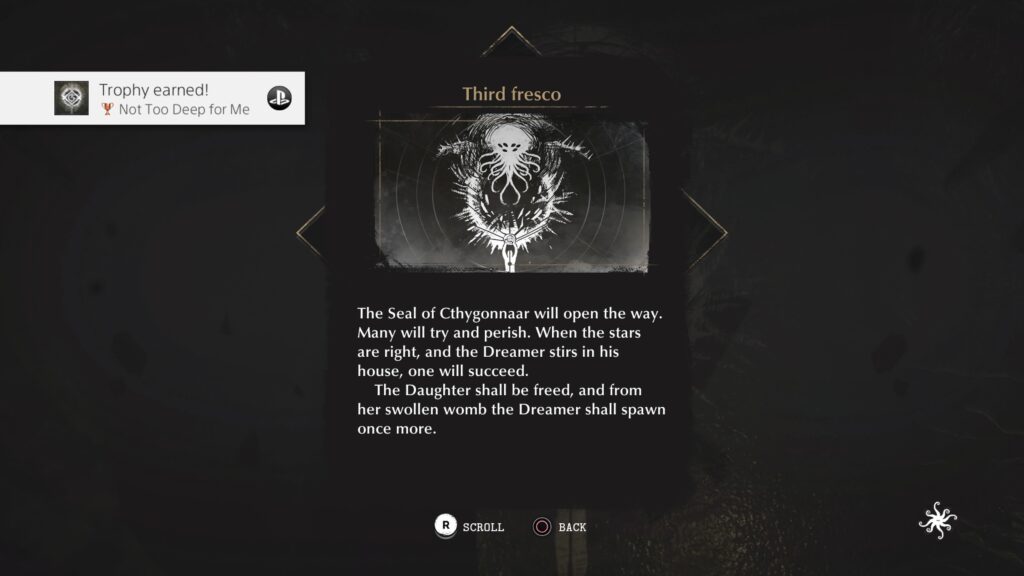

Without question, the game’s strengths are the story and characters. The gamer controls Charles Reed, an ex-sailor-turned-PI who travels to Oakmont, Massachusetts to learn about nightmarish visions that have plagued him since his time in the Navy. Reed’s first point of contact is a flamboyant German professor named Johannes van der Berg, who is dressed in a less-than-subtle yellow suit that fans of the Cthulhu Mythos will immediately recognize. In any event, Oakmont is an amalgamation of multiple towns in Lovecraft’s fiction, and it plays an ominous role in The Sinking City because it’s, well, sinking. That is, a terrible flood ravaged Oakmont months before Reed’s arrival that not only makes travel difficult (many locales must be accessed by boat), but also produced ideal living conditions for dangerous monsters called Wylebeasts. Although there are multiple subquests scattered throughout the game, the primary mission is to uncover what dwells beneath Oakmont and why it drives any who encounter it insane. The “it” here is associated with “You Know Who,” but his prophesized resurrection in The Sinking City involves stories that became part of the canon decades after Lovecraft died. I won’t spoil anything, but rest assured that you will see many images and frescoes of tentacled deities (no, not hentai).

The story is solid, and this is owed to some conflicted characters. While many of these characters aren’t exactly profound, they are complex because their motivations inform the gamer that many of Oakmont’s residents aren’t good people. You can expect to encounter zealous cultists, corrupt politicians and police officers, mad scientists, murderers, and more. These interactions are sometimes uncomfortable as the Ku Klux Klan also has a presence in Oakmont, a contentious point that the developers note in a disclaimer at the beginning of the game (in one mission, Reed can eradicate their entire leadership). Nevertheless, many of these complicated characters directly speak to the apocalyptic issues plaguing Oakmont after the flood. As an outsider, Reed can try to help (to advance the story), but many of the choices raise moral and ethical concerns as the city descends further into chaos.

Gameworld and Gameplay

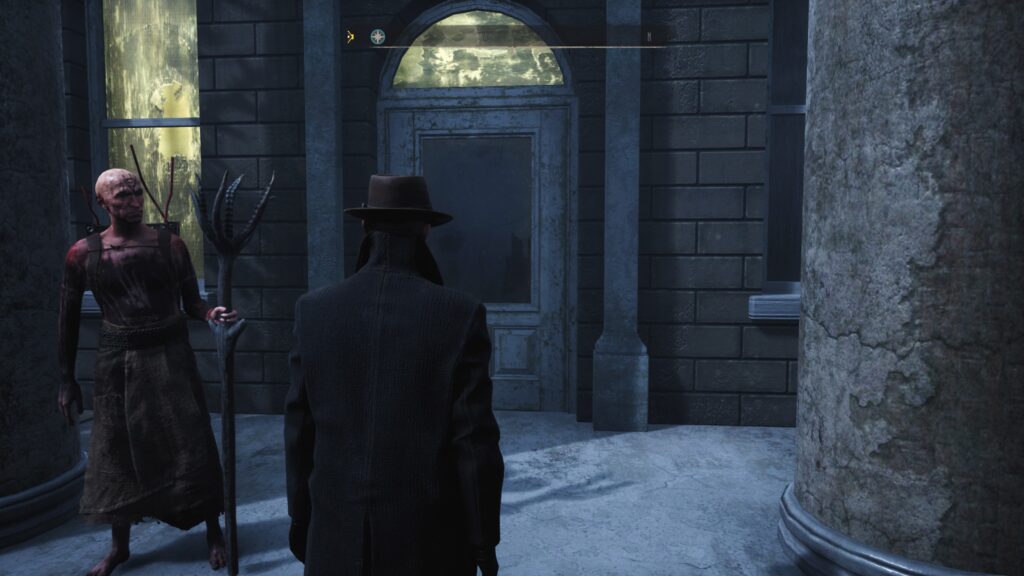

Before I address some of these choices, I’ll briefly discuss the gameworld and gameplay. First, the world itself is vast as Frogwares apparently used Unreal to generate a city like other open-world titles. The result is a cool setting that often has cool atmospheric qualities like fog, weather, and NPCs going about their business in the 1920s. if you picture a town like Silent Hill without the Otherworld and the residents somehow corralled the beasts into specific infested areas, you’ll get a general idea of at least one of Oakmont’s many problems. To be certain, the gameworld is bleak as the inhabitants had to alter their ways of life after the devastating flood. For example, several of the streets are flooded, so the residents set up boats to get from one point to another. Yet while the inhabitants struggle with their isolation, watching NPCs go about their business in a post-apocalyptic world also demonstrates a unique and stubborn desire to cling to existence. However, while the vibe and atmosphere certainly are intriguing from an open-world, survival horror perspective, there are complications. For example, Reed can interact with only a couple of NPCs scattered throughout the gameworld. Additionally, those he can interact with will cycle through a couple dialogue options before or after he completes a quest. All other NPCs are essentially husks. Additionally, while the world itself is huge, traveling through it can be a nuisance as Reed will often have to walk up to a boat, drive to a vague location on the map, disembark, and repeat the same process ad nauseum (there are some fast travel markers scattered throughout the gameworld). Further, while the game tries to carve Oakmont into distinct districts as if to showcase the haves and have-nots of the society, the districts and buildings all begin to look similar after extended periods of play. I suspect that this might have been an issue with scope creep as the goal was to create a huge environment, but by doing so, it’s hard to differentiate between a district like Advent, which has city hall, and Reed Heights, a seemingly upscale but ultimately inaccessible borough.

This brings me to the game’s gameplay as gamers control Reed via a 3rd-person, over-the-shoulder perspective. If you’ve played games like Assassin’s Creed, The Last of Us, and Silent Hill: Homecoming, you know what to expect. In fact, the circular equipment management system immediately reminded me of Homecoming. Ultimately, The Sinking City’s gameplay is an amalgamation of similar games. For example, there is a crafting system in which the gamer collects scattered junk to create weapons, ammo, and first aid kits. Although materials are initially scant, they become easier to find once the gamer begins to mark relootable treasure boxes on the world map. There’s also a leveling up system that allows gamers to pump stat points into certain skills. Experience increases by talking with NPCs, discovering locations on the world map, finishing a main quest, and completing a subquest. Leveling up isn’t without its own issues, however, as some skills are entirely pointless. For example, some skills allow Reed to stay in water longer or to recover after a bad fall. I never once found any need for either of those skills given that the game never really placed me in a situation that validated their use.

Over time, I felt that experience points disproportionately favored subquests because I had initial troubles leveling up until I experienced what the extended stories had to offer. Let’s just say that after a couple subquests, you’ll get all of the skills you need/want, and you’ll never be hurting for ammo or crafting materials. That said, whether it’s a main quest or a subquest, I hope you like fetch quests, because that’s all you’re going to get in The Sinking City. Need to find someone? Fetch quest. Need to locate a main quest item? Fetch quest. Need to find letters written by residents around town? Oh, do we have a fetch quest for that! You get the idea. Suffice it to say, things became a little tedious leading up to the final chapters. Some of these fetch quests even force the gamer to travel underwater to uncover eerie caves. This ocean world is cool and creepy, but it’s also monotonous as gamers will control Reed in a clunky diving suit roughly six times over the course of the game before returning to the world above.

On one final note, combat is competent but clunky. I stuck with guns and didn’t bother setting traps or throwing projectiles like bricks or Molotov cocktails. Some monsters will manage to sneak in some cheap hits in combat, but I found that most of those were attributed to Reed having to reload in close quarters after one or two shots with weapons like the shotgun and rifle. For me, the strangest facet of combat was the randomness of it all. For example, I went nearly half the game without even needing to fight Wylebeasts or humans and when I did, most were simple skirmishes. However, during certain events, the game begins to throw difficult fights at the gamer when it felt like they didn’t even have to engage enemies initially if they didn’t want to. I learned after consulting a walkthrough that enemy placement is random in The Sinking City, and some later chapters included extreme firefights as a result. These random elements ultimately produced an inconsistent combat experience as the final battle in my playthrough had like five enemies that were disposed of pretty quickly. When I played, I was primarily interested in advancing the story, so be prepared that the game will occasionally throw nasty surprises your way if you only want to complete the story.

Choices: Damned If You Do, Damned If You Don’t

Like all Lovecraftian yarns, The Sinking City meanders; on several occasions, the storyline has nothing to do with cosmic horror. Yet, as previously stated, one of the game’s primary strengths is a colorful cast of characters. For example, Innsmouthers, based on the novella The Shadow over Innsmouth, are literally half-fish, and the socialite, Robert Throgmorton, is an ape based on the short story “Facts Concerning the Late Arthur Jermyn and His Family.” While the anti-interracial subtext of these original stories is awful, The Sinking City eschews the race-baiting background of Lovecraft’s works to construct its own lore and context, thereby creating a world that is fairly common in fantasy entertainment. Ultimately, however, the rival factions in the game produce choice scenarios that 1) are rarely crystal clear, and 2) force the gamer to question what they believe is the lesser of two in-game evils. It’s difficult to discuss some of these choices as they will spoil several plot points, but one such choice involves siding with a bitter, delusional, and deranged lunatic or an actual cult known for various atrocities. Siding with the lunatic means you do something unconscionably evil to eliminate/expose the cult, but siding with the cult means, well, siding with the cult! There were moments in the game where I seriously had to stop and contemplate my options because there wasn’t a moral solution. Admittedly, this is a unique feature in the game as I would argue these scenarios make the gamer interrogate some terrible options, but the delivery is flawed because the final decisions never feel truly consequential as the game just continues to progress towards one of three endings. While it would be neat if choices affected the outcome, this isn’t the case. In fact, the gamer can literally save before the final underwater quest and just view all three (bad) endings in succession. You either awaken your tentacled overlord or you don’t, and nothing you previously did matters. Ultimately, the choices seem heavy, but most are missed opportunities for serious ethical decision-making in game design.

Cool Genre Mechanics?

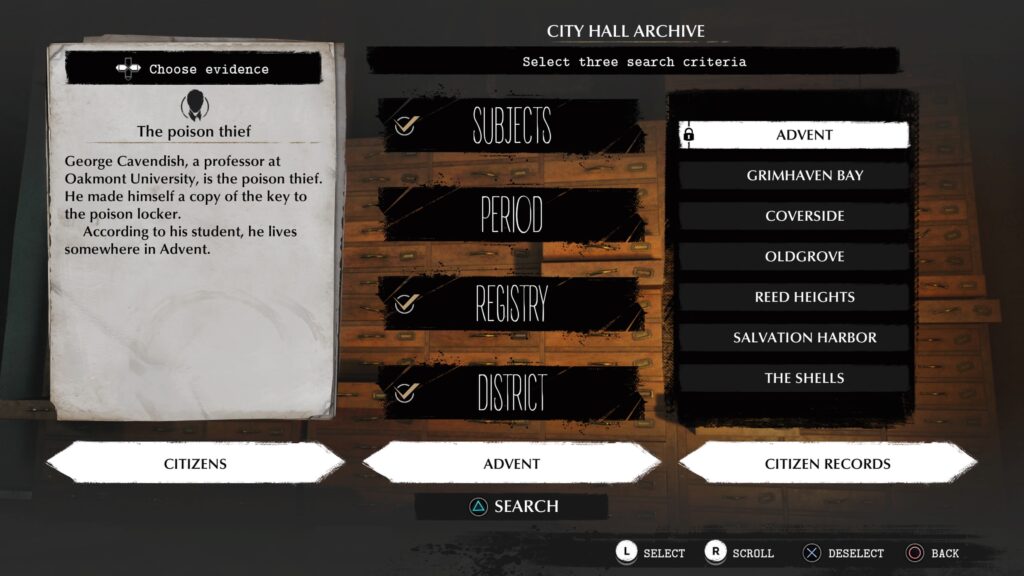

As previously stated, The Sinking City is an open-world, action-adventure, survival horror game, so it’s technically already a genre melder. While it does have flaws, features of those three genres are visible. Yet what I thought was neat about The Sinking City is how it incorporated some narrative adventure game elements to advance the story. First, gamers can access Reed’s “Mind Palace,” which allows him to piece together clues. On occasion, some of these clues present different possibilities. While you don’t technically have to access the Mind Palace to advance the story, seeing the options in advance before arriving at the decision is an interesting touch. Second, on multiple occasions, the gamer will have to go to locations that have “Archives” in which the correct input of options will produce a newspaper clipping about where to go next. While some may find these features tedious, I actually appreciated them and wonder what the game would have been like if they were more fleshed out.

Final Thoughts

I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention that The Sinking City was a bit too long (like this review, am I right?!). After a while, some of the main quests either felt like filler or repeated. This is to say nothing about the fact that the slightest incursion can make Reed’s “sanity” meter fall, including merely opening a door to a new room or unlocking a new clue. We get it, y’all. He’s unstable. Further, there is some troubling subject matter that the developers even mention in a disclaimer at the beginning of the game. For example, the Ku Klux Klan is visible in Oakmont. While the mission in which you smoke them is satisfying, their inclusion is certainly a trigger warning. Nevertheless, I enjoyed my time with The Sinking City. Lovecraftian games (and movies) are hard to make, but The Sinking City’s setting, story, and characters work together to make a compelling argument that this is how such a game should look. If you are a fan of cosmic horror, I recommend giving this one a whirl because it’s currently the best Lovecraftian game out there, even with its flaws.