Breath of Fire: Dragon Quarter

Breath of Fire: Dragon Quarter

When the backlog becomes intimidating, make someone else play a game for you!

Mark’s Note: This guest review is part of a potential series in which I commission games I own to friends who have played them because I probably will never get around to doing so. This first review is by Day Devereux. We met through a plethora of Suikoden forums in 2006, starting with Their Star, then Suikox, and finally Due Fiumi before the series died (okay, so I revealed that it already died in my review of Suikoden V, but we were still clinging to hope!). Since then, I’ve kept in touch with Day, who was kind enough to play Breath of Fire: Dragon Quarter on my behalf. I actually love (loved?) the Breath of Fire franchise. The first game was among my first SNES RPGs. The second game was among the worst translated games I have ever played, but it improved on a lot of issues I had with the first game. I would honestly consider Breath of Fire III to be one of the best RPGs for the PSX, so go play that if you haven’t already done so. Finally, although I own Breath of Fire IV and have heard great things, I just can’t seem to jump into it. Enter Dragon Quarter, which is arguably the most polarizing game in the franchise. I believe Day’s review will be much more illuminating because I played for an hour before I gave up. Will Day’s review convince me to try my luck again? I dunno. This game was hard as hell to the point that it almost taunted you to stop playing.

"This Is a Tiny Tale of Time": Breath of Fire Quirks

With those words, Breath of Fire: Dragon Quarter (Breath of Fire V: Dragon Quarter in Japan) begins. A covenant is made with the player with these words, such as a covenant is made between the protagonist, Ryu, and the dragon (Dragon half? We'll get there), Odjn. The covenant between game and player is that of a smaller, more intimate experience than previous Breath of Fire games. Breath of Fire is a Japanese role-playing game series dating back to 1993 with the release of the first title on the Super Nintendo.Three sequels would follow, the first appearing on the Super Nintendo in 1994, and two more being released on the Sony PlayStation in 1997 and 2000. These games could broadly be categorised as fantasy titles, brimming with color and lively, well-animated pixel sprite graphics. Although vague gestures towards technologically advanced "ancients" and their strange devices would make occasional appearances, Breath of Fire was a series firmly established in the realms of fantasy; of winged humans, magic spells, and dragons.

And dragons, and dragons, and dragons. The titular "Breath of Fire" is that of a dragon, after all, and every protagonist has the power (and burden) of being that dragon. Very beneficial for slamming dudes in turn-based battles, a detriment when mulling about the nature of one's humanity.

The last quirk of the Breath of Fire series before we dig deep into its fifth entry is its repurposing of characters. Every game features a main protagonist called Ryu (although you can change the name), and a winged princess named Nina. Other names (such as the goddess Deis/Bleu) and species (the greedy fish-like Manillo and the playful, charming faeries) also make recurring appearances. Takes on whether Breath of Fire shares the same world has tended to vary over the years, though it is generally accepted that the first three games broadly work as a trilogy and that you could make the other games fit in around them.

Aesthetically, Dragon Quarter employs cel-shading that resembles Wild Arms 3.

If this is the point where you expect me to say, "Forget all that, because Dragon Quarter is off the rails!" then apologies must be made. What makes Dragon Quarter such a fascinating game is partly what it chooses to jettison and what it chooses to retain from its predecessors.

Concerning War Between Friends (and RPG Traits)

Breath of Fire: Dragon Quarter, in stark contrast to its ancestors, is a science-fiction RPG, low on exploration and high on strategic combat. Taking place in the underground world of Deepearth, Dragon Quarter is a world in which people have never known the sky. It is a truly claustrophobic world of tunnels and sporadic settlements, drilling down through over 1000 meters of soil and rock. Large gates guard the only opening to the decimated outside world, the result of a calamity involving dragons.The might of these dragons is both feared and revered in equal measure. In this world, some rare people can "junction" with what are called "dragon constructs." The entire caste system of Deepearth is based on this possibility with every citizen having their "D-Ratio" on file, from 1/16384 to the highest possible D-Ratio, the titular Dragon Quarter, 1/4.

We're quickly introduced to Ryu, no longer the brash warrior-child of previous titles, but an emaciated Ranger, grunt, D-Ratio 1/8192, a Low-Sector nobody evaluated and classified as such since birth. We also meet Bosch, Ranger, D-Ratio 1/64, the son of one of Deepearth's Viceroys, friend, and whose stint as a Ranger is a stepping stone as he ascends the ranks to claim the privileges that are his by birthright. (The localization misses a beat here. Bosch shares the same Japanese name as the character Bow from the first two games. All three characters serve as Ryu's stalwart companion.) What is supposed to be a routine cargo escort mission turns into (of course) much more, as the cargo is attacked by anti-government terrorist group Trinity, Ryu is separated from his friends, and comes to discover the cargo is a mute, winged child, clothed in a dirty white dress and far more emaciated than Ryu himself, named Nina. While attempting to climb back to Low-Sector, Ryu grows attached to Nina and their Trinity agent, Lin, and when Ryu discovers what is causing Nina's coughing fits and bouts of frailty, endeavours to bring her to the surface, putting him in stark opposition to his former colleagues and the entire hierarchy of Deepearth.

Destiny Decided to Challenge Us (Except Mark Who Stopped Playing)

Thankfully, Ryu doesn't have to go it alone. Although joined by Nina, as a useful mage, and Lin as a ranged attacker with her pistols, Ryu's real ace-in-the-hole comes following a fateful encounter with the corpse of the dragon-half, Odjn. In the lore of Dragon Quarter, a dragon half, or dragon construct, is the last remnants of the dragons in the world. Seemingly a mix of bio-technology and machinery, these dragon halves (D-Ratio 1/2) are able to bequeath their power to worthy humans for a cause, and a price. Which mostly means you get rad dragon powers and transformations like in previous games. Cool! Oh, and the transformation will slowly consume you from the inside-out, killing you in the process. Uncool! From the moment you first gain your dragon powers, a percentage counter will constantly tick up over the course of the game. Exploring the world, navigating dungeons, fighting battles…it doesn't matter (The D-Counter increased by 0.01% every 20 steps, or per turn in battle). That D-Counter will keep filling, with rapid bursts if you utilize those dragon powers. When it hits 100%? Game over.

That's where the second aspect of Dragon Quarter's gameplay comes into play: the Scenario Overlay system (SOL). Yes, the same one Dead Rising would later use. When the player is pushed into a no-win scenario, you can restart the game with your equipment, skills, and other items and money, giving you a leg-up on your next attempt. Additional scenes are also available through SOL, shining a brighter light on the world of Deepearth and its inhabitants, further encouraging retrying.

For battles themselves, Dragon Quarter utilizes a combination of real-time strategy and turn-based combat in what is called the Positive Encounter and Tactics System (PETS). On the map, enemies and players can maneuver at will with the player being able to set traps, lures, et cetera, to gain an advantage over their enemies before engaging. Once the player and the enemy interact, the combat switches to a tactical system where characters spend AP to move around the field and launch attacks at their opponent. With sufficient planning, battles are much easier, or won outright before they are even fought.

When you combine the setting and the gameplay, what you get is a slow climb. A war of attrition as you attempt to scale to the peak of Deepearth, managing resources, planning enemy encounters, and strategically deciding when to break out your dragon powers, all while attempting to unravel the secrets of Deepearth and the conspiracies machinated by Regent Elyon, a dragon quarter who once linked with Odjn but at the final, crucial moment turned his back on opening the way to the sky.

And So We Choose to End the World

Dragon Quarter is a dark, gloomy game, as much in terms of content as aesthetics. The fundamental despair and decay of Deepearth is communicated early and often. Even the supposedly well-off areas, such as Mid-Sector, are clearly in decay, fallen from whatever middle-class veneer they may once have held. Solutions to Deepearth's woes, such as air quality in the lower levels, are also distressingly bleak. The moment when it is revealed that Nina, as a 12-year-old low D-Ratio, was taken and genetically engineered, her wings actually being what used to be her lungs, now repurposed to act as an air filtration unit, her vocal cords removed to dehumanize her, is one of the single bleakest reveals in a JRPG that I can remember.

This is sort of depressing, Day...

The possibility of rebel group Trinity being a false flag operation used to direct the energies of the disaffected, the reveals surrounding the true nature of linking with a dragon, the efforts of Bosch to defeat you while growing more unhinged from having his caste-centered world view dashed, and even aspects of the ending all draw on this sense of despair. Ryu's hope, meanwhile, is single-minded. Even with all his power, Ryu has no real determination to overthrow the government, or open Deepearth to all, or to tear down the caste system that oppressed him and others. His goal is simply to get Nina to the surface, in the hope that enough time has passed that the air there is clean enough for her to survive. Or is that the case? As Regent Elyon notes, a dragon, even a dragon half, is a powerful creature, and who knows who is really in control of events?

In Order to Meet Our Mortality

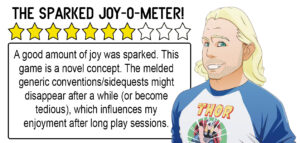

Dragon Quarter is not without its mechanical weaknesses. Its skill system is lopsided, with high-level, high-cost abilities often paling in comparison to simply spamming more basic, but lower AP consuming techniques, discouraging truly diving into the games skill and combo systems. Graphically, the game is highly atmospheric and gloomy, but sometimes to the point of rendering the screen difficult to navigate or comprehend. And despite the presence of the SOL system, no-win scenarios can be frustrating, especially when it forces you to replay large swathes of the game again (though it is very possible to beat the game in a single run). Much of the story and setting of Dragon Quarter also must be inferred rather than told to the player outright. Exploration, side-conversations and expository monologues are each a rarity in Deepearth, which holds only a handful of settlements and is characterized by its climb through old mining tunnels and industrial zones.

There Was Nothing to Regret

Removed from its initial 2002 reaction, which was mostly negative backlash from a fanbase that was, on the whole, pleased with the far more traditional, princess rescuing, ancient emperor fighting (but still subversive in its own way), Breath of Fire IV, Dragon Quarter today still remains something of an enigma. Headed by series veteran Makoto Ikehara, who was inspired to create the game's setting after reading the 1994 alternate history novel Gofungo no Sekai (The World Five Minutes From Now), Dragon Quarter was designed to be a challenging game in contrast to its predecessors. What Dragon Quarter does, and does quite well, is to take the expectations and beats of a 'standard' Breath of Fire game, and twist and strain them to see what remains, to see how they can stand up to real scrutiny. Despite a lack of a dialogue, the bonds between Ryu, Nina, and Lin, the jealousies between Ryu and Bosch, the officious yet nurturing leadership of Captain Zeno, are real relationships, as meaningful as any throughout the game. I believe it’s those bonds, especially the bond between Ryu and Nina, that is the core through line of the game. This bond functions as the game's narrative and emotional core. The gauntlet that Ryu must endure is the same gauntlet the player must struggle through; unrelenting battles, and pursuit, and climbing, and brief reprieves to rest and take stock.

Nothing...

This can be overwhelming and, depending on the player, just plain unfun, but as I last played the game, I found that climb exhilarating and the urge to keep everyone safe genuinely emerging in me. As I made it through the final encounters in the game, as the freight elevators took me closer and closer to my goal, all while my D-Counter ticked closer and closer to certain death while I fended off the final, most powerful bastions of resistance, I think I found what Breath of Fire: Dragon Quarter was always trying to impart. The struggle in Dragon Quarter is not a failure on your part, or the games. The struggle is the point. Ryu's journey is the player's journey, not one you are simply observing. As such, the game tries to impart that conflict on the player as well.

Dragon Quarter is far from a perfect, for reasons outlined above. It is sometimes frustratingly obtuse and was fundamentally designed to make the player quit at least once. It also infuses that ethos to all aspects of the game world, creating a fleeting, but realized experience for those able to keep climbing.

Keep climbing, dear player, and the sky may await you.

(This is Day's score. I just work here.)

It still gets a flaccid penis out of 10 from me…

If ya think I wanna replay the game over and over just to get farther each time, you’re high as angel pussy, man…

I’m with you on this one, Mark. I played for an hour and gave up. I *loved* BoF3 when I first played it, though. With this one, I just remember immediately being lost.